The Secret Life of Beans

Or, how they get to your table... an insight into American Agriculture

In America, we tend to think of beans as “cheap” food.

Or, at least inexpensive—they are the epitome of budget eating and are often used to stretch a meal.

The American Agriculture model wants you to think of them as “cheap.”

But beans are actually an energetically expensive food. It takes quite a bit of land to grow enough beans to have a good harvest.

And then there’s the weeding - OMG the weeding!

Not only does this delightful summer activity give you a glimpse into an entirely different world, it opens a door of understanding about why organic food from small, local farms is priced the way it is.

For non-organic sources, I suppose weeding is replaced with a few hundred pounds of herbicide sprayed on the whole field, but I don’t know exactly what goes into the chemical-dependent process.

But for the organic grower, this process is always physically laborious and time-consuming.

The beans grow, but so do the weeds, again.

Finally, it’s harvest time.

We modern humans have made this harvest somewhat more efficient with various machinery.

But it still takes time and timing.

Beans need to dry. Which means that they must be harvested and dried at the right time, not when it’s most convenient.

As with any mechanized process, there’s a trade off. Yes, it’s not as laborious (and thank goodness for that!), but then you have inevitable losses from a mechanical process that damages some of the harvest.

Once harvested, it’s time for the first sorting and cleaning. Again, this is usually mechanical. Thankfully so!

But the sorter will usually miss some in the sorting process, including many of the ones slightly damaged by the mechanical harvester.

By the time planting, weeding, harvesting, drying, sorting, and cleaning are all done, you’ve got hundreds of hours invested on even a few acres.

But you’re still not done.

About ¼-⅓ of the beans are too damaged or blemished to make the final cut. That’s where hand sorting comes in.

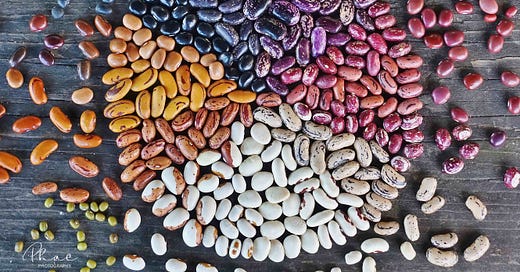

These beauties are one of my favorites—an heirloom, cranberry-type called Red Soldier Bean, apparently named because someone thought the Rorschach-like blot on them resembled a toy soldier. 🤔 Do you see it?

The above pic is just before the final sorting.

And this one is mostly through the final sorting. Can you see the difference?

This sorting is best done in small increments. Or around a table with others so you can socialize while you do this repetitive work. It’s a strain on the upper back, neck, and eyes as you lean down to pick out the rejects.

Finally, it’s ready to bag and label for sale.

$10-15 per pound—depending on the variety and how decent the yield was that year—is not unrealistic for the labor, land, expertise, and love that goes into bringing a bean like this to your table. If that price sounds steep, many farms will offer a separate pricing structure for “seconds” - products that don’t meet their criteria for retail sale. Seconds are a fantastic way to get more for less and add your own labor to the final product.

Food isn’t energetically cheap.

It never has been and it won’t be.

Good food is valuable.

Especially organically grown heirloom products.

Good food nourish our soils and our souls. Good food brings people together in the field, in the barn, and at the table. Good food allows you to explore the complex flavors and beautiful visuals that diversity offers us. Good food is satisfying and nourishing, not extractive and wasteful.

And it won’t make you feel terrible for eating it or after eating it.

Good food is valuable and it cannot be made cheap.