Is This One Brand from 1911 the Reason for Fake Food Today?

The poisoning of American minds and bodies

Eli Whitney, James Norris Gamble, and Thomas Edison were clever men. As inventors and businessmen, they paved a trail for the demise of American minds and bodies. Where their lives overlapped, they opened the portal to a new kind of death and destruction that America had never seen.

James Norris Gamble’s use of industrial waste as consumables mass marketed to an unsuspecting American public turned our bodies into depositories of unwanted materials that continues to this day.

How did it start?

Eli Whitney patented the cotton gin in 1794. This machine removed the cotton seeds from the cotton fiber quickly and efficiently. Until this time, it was humans–mostly slaves–doing this work. With the mechanical invention, seed removal happened far quicker providing more cotton–and more seeds–to the business owners.

James Norris Gamble was a soap and candle maker and a chemist by training. He was the son of half of the Procter and Gamble brother-in-law duo that founded the company in 1837. The company quickly became famous for the soap and the candles they made in their Cincinnati factory. At that time, these products were made from animal fats–mostly lard and tallow. As a center of the rapidly evolving meat packing industry, Cincinnati naturally had a boom of other industries supported by the by-product of animal processing. James Norris Gamble became vice president of the company in 1890.

Thomas Edison, of course, patented the long-lasting incandescent light bulb which we all know him for.

These 3 inventors altered the American food scape irreparably and ushered in a calamity from which we will likely never recover.

Here’s what happened:

With the help of the cotton gin, cotton seeds – the waste product from cotton manufacturing – became a problem textile companies had to deal with.

Some aspiring industrialists had already learned how to extract the small bits of oil from the cotton seeds. But James N Gamble and German chemist E.C. Kayser tackled the issue of making it stable enough to use for soap and candles. By 1904, they had perfected their technique of hydrogenating the cotton seed oil so it was firm enough to use in soap and candle making. (Some credit the floating of Ivory soap to the hydrogenated oil used in their making).

At the same time, Thomas Edison’s incandescent lightbulb was making candles obsolete. But, the cotton seeds kept on coming. What would they do with all that cottonseed oil and no more demand for candles?

What happened next should be a story that we never forget.

In 1911, after some research and more chemistry experimentation, Procter and Gamble launched Crisco–Crystalized Cotton Seed Oil for sale to the American public.

Remember, this entire product came from an industrial waste product – unwanted cotton seeds. Cotton seeds, over the course of history, was nothing that humans had incorporated into their diets, ever. In fact, cottonseeds up to that point contained a toxic phytochemical called gossypol.

To put things into perspective, gossypol toxicosis in humans is linked to adverse effects on the cardiac, hepatic, renal, reproductive, and/or other symptoms. Prolonged exposure can cause acute heart failure resulting from cardiac necrosis. Also, a form of cardiac conduction failure similar to hyperkalemic heart failure can result in sudden death.1

There are a few other key details that were at play during this time. The 1906 publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, began to discourage people from using traditional lard, which, until this point, was a staple in many non-Jewish households. In American cities, new waves of Jewish and other ethnic immigrants were arriving regularly, who avoided lard for religious reasons.

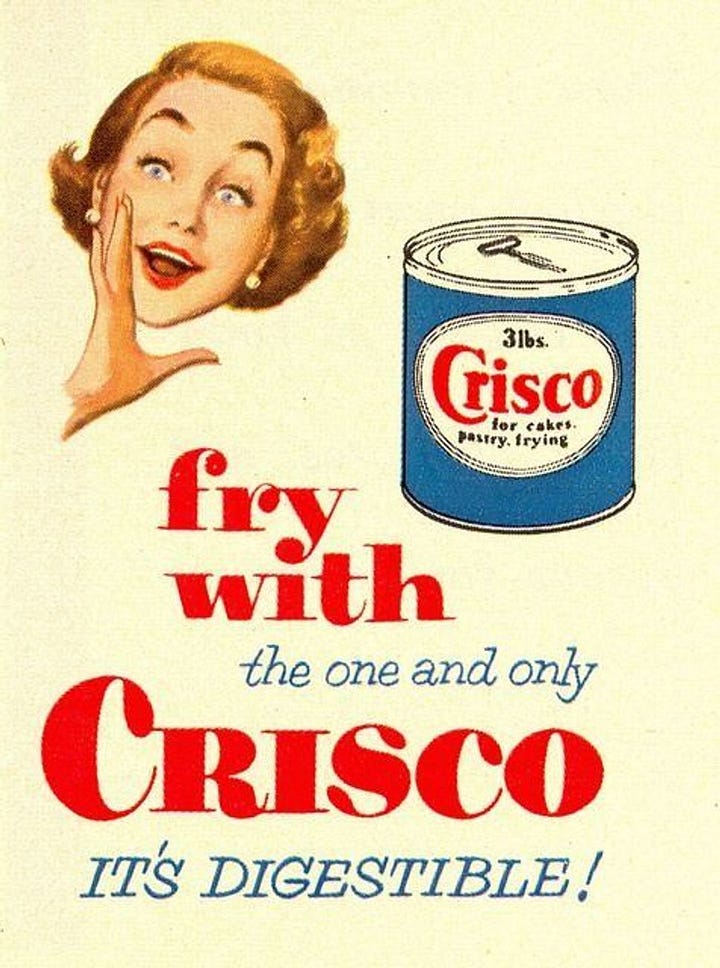

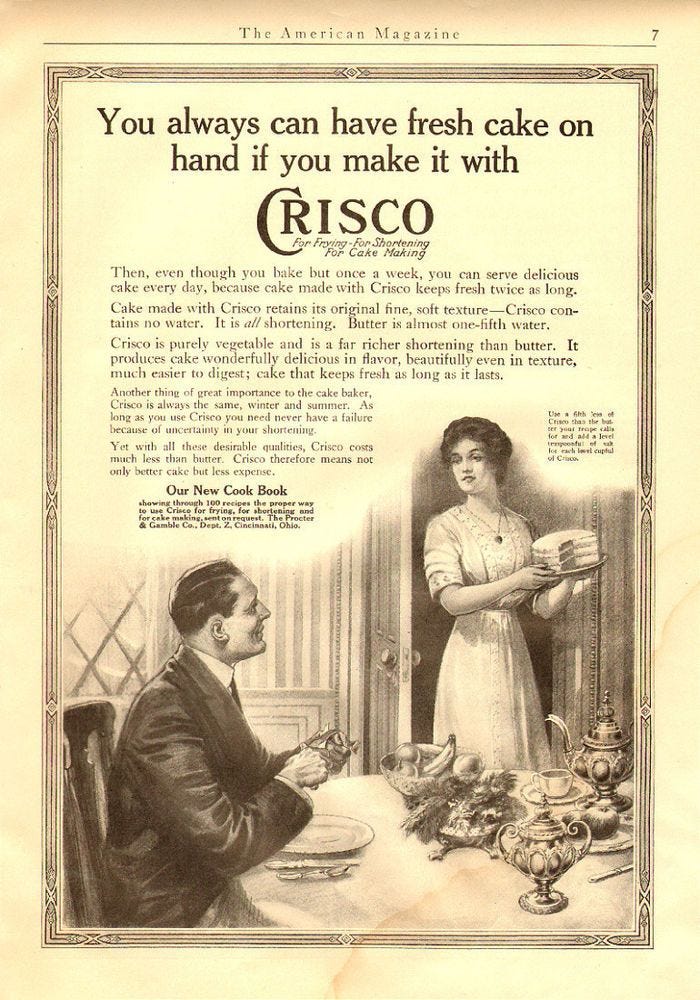

Crisco looked and behaved like lard. But it was not lard. The company packaged their hydrogenated cottonseed oil in cans and started selling it as a “healthy” food to use in place of lard.

The marketing campaign was just beginning. Procter and Gamble hired the famous J Walter Thompson advertising agency.

In 1912, with the help of said agency, they published a cookbook to go with their new Crisco product. A Calendar of Dinners by Marion Harris Neil contained 615 recipes and lovely illustrations.

But perhaps it was the 30 pages of advertising at the beginning of the book that began to sway popular opinion.2

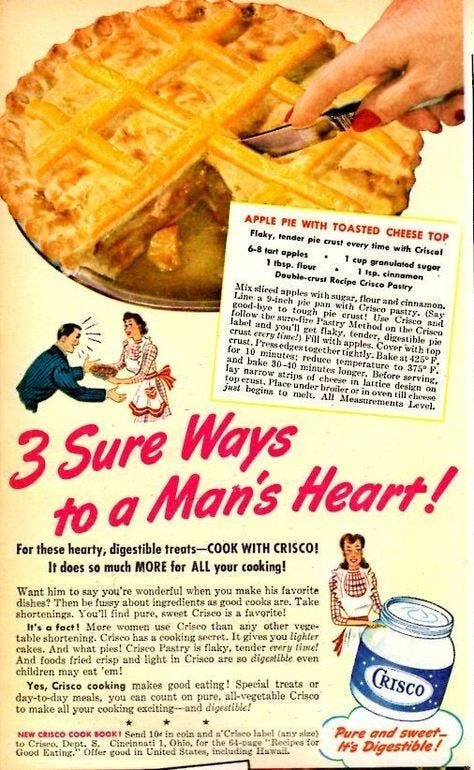

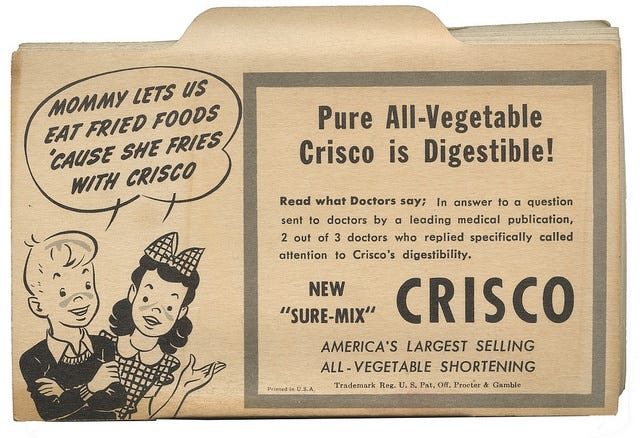

The marketing agency carefully wrote content extolling the virtues of the “pure white” fat and making preposterous claims that it was “more digestible” and “healthier” than other fats. The words were selected carefully to appeal to and manipulate the women reading it. They included pressure that children should get this fat–especially girls who were sometimes picky.

They published excerpts for different audiences. A shorter book was one example. They had it translated into several languages to appeal to the diverse populations growing in America. They printed copies in both Hebrew and English to target the Jewish housewives who they saw as prime customers since they never used lard anyway.

The advertising agency published stories about how great Crisco was, testimonials from Rabbis and doctors, and a plethora of ads making health claims about Crisco.

But they didn’t stop there. They shipped their cookbook and a container of Crisco to households all across America.

In short, this was the most aggressive marketing campaign to date. And it worked.

“The unprecedented product rollout resulted in the sales of 2.6 million pounds of Crisco in 1912 and 60 million pounds just four years later.”3

This feels like the roller coaster that keeps on going. But it didn’t stop there. Crisco was selling just fine, but more is always better, right?

An unholy alliance formed between the company and the newly formed American Heart Association (AHA). “In 1948, thanks to being the beneficiary of the Procter and Gamble sponsored “Walking Man” radio contest, the AHA went national with a $1.75 million dollar windfall. A national fund raising campaign in 1949 netted another $2.7 million and the AHA never looked back.”

With this new relationship, the AHA began demonizing butter and lard giving a greater push to the sales of Crisco.

At the time, Procter and Gamble were spending a lot of marketing dollars on radio ads. Procter and Gamble (likely through their ad agency), first created radio dramas, later becoming primary sponsors of television “soap operas.”4 Of course, they were still in the soap business so it made sense for them to keep marketing their soap products.

The launch of Crisco happened approximately 17 years before Edward Bernays published his famous book “Propaganda.” No doubt Bernays, the J Walter Thompson Advertising agency, and Procter and Gamble all understood the gains to be had from propaganda on an unsuspecting population.

Although the Crisco cookbook was ghost written by some of the most studied and prolific copywriters and advertisers of the time, it was a woman’s byline. It was targeted to women.

Women had– and have– incredible power. Both persuasion power and spending power. Propagandists know this. They knew that without women’s enthusiastic support of this fake food, it would not be adopted.

Crisco enjoyed a widely profitable run in the American landscape–and indeed many others–before the truth of the scientific claims could catch up to the propaganda in the late 1900s. As an old proverb says “A lie will go round the world while truth is pulling its boots on.” This seems apt in this situation as well.

But that was over 100 years ago, this could never happen today, right?

There are people who readily use the tools of propaganda to push products on a trusting population. Indeed, some continue to make outlandish health claims without any merits.

As Crisco diminished in popularity, other items quickly filled the void. Our homes, farms and bodies are inundated with industrial waste turned into consumer “goods” many of them designed to be “foods” for our tables.

It saddens me that our food system is in this state of affairs right now.

So how do we acquire safe foods?

The best thing you can do to protect yourself and your family is to understand propaganda. It’s everywhere and it started a long time ago.

Armed with that knowledge, take action by supporting your small, local farms who will be transparent with you and not propagandize you into buying “food” that isn’t food. And, of course, grow some of your own food.

May wisdom prevail.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4033412/

https://archive.org/details/calendarofdinner00neil_0/page/8/mode/2up

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2012/04/how-vegetable-oils-replaced-animal-fats-in-the-american-diet/256155/

https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/2017/10/04/our-history-p-g-put-soap-soap-opera/732149001/

Thank you, tremendously, Liz!

Although the ingredients today appear to have changed the company still compares it to butter as if their product is better: https://crisco.com/product/all-vegetable-shortening/. They are able to do that only because of the misinformation about animal fats plus propagandizing their displacing products .

All of this underscores the utter failure of public education that (like these food companies) are propagandizing to the detriment of people.

-

Appreciated every word of this. My mom used Crisco a lot when I was growing up.